“Do not ask who I am and do not ask me to remain the same: leave it to our bureaucrats and our police to see that our papers are in order.”

— Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge

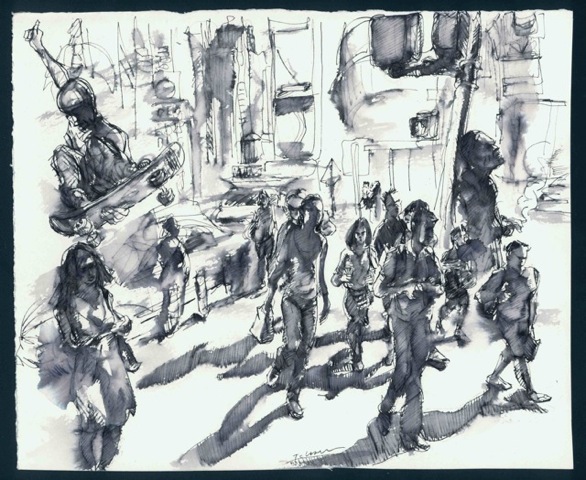

Tom Christopher has always had his eye on the city, his finger on the changing rhythms of its pulse. His daylight noir paintings chronicle the allure of New York: its beauty, color, vibrant activity. But the figures that people his canvases belie the surface glamour as they go through the circuit of their days. Each seems attuned to his or her own story, a recitation of dreams and loss that loops incessantly.

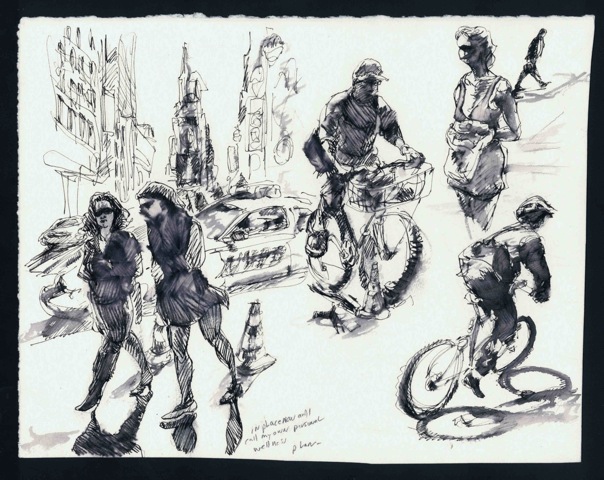

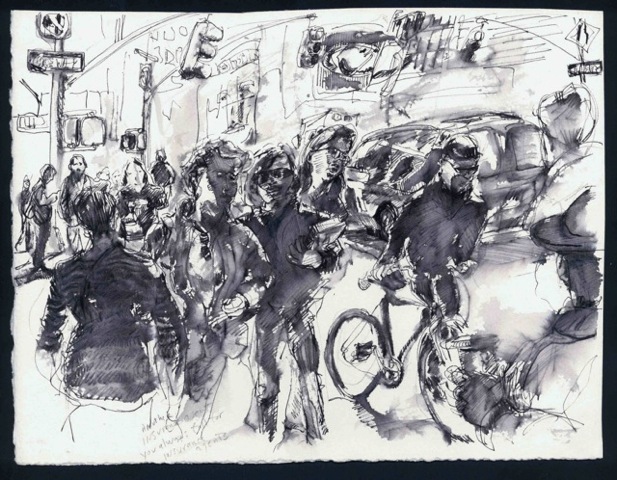

The titles of Christopher’s paintings, eavesdroppings caught as they fall, are shards of commentary that offer us a glimpse into the lives of these characters who inhabit the city. Christopher’s career as a courtroom artist honed his capacity for empathy. Attuned to the moments and gestures that shed light on the depths of human emotion, he understands that a day can turn on a dime; his art, in part, seems to exist to catch that turn. This perhaps explains why he lets his drawing show—as if the pencil lines map the real, yet unseen city, where anguish strolls every avenue, and false prospects and broken promises are a web of streets that stick to us and trail behind. The deliberate splashes of colors on his canvases articulate and mimic the frenetic pace of the city, suggesting that there’s no time to go back, to go over, no studio in which to collect one’s sketches and make sense of them in a stately, methodical, academic manner.

Now, more than ever, the mechanism of the city never winds down. The new world is dominated by the split screen and the ticker crawl. The increments of time seem shorter every day. Reputations are made and lost on Facebook; revolutions ignite in a Tweet— 140 characters or less. Once upon a time, only a homeless crazy would walk around ranting aloud about nothing to no one. Now every ear is glued to a cellphone. If the city is too much to take, you can check the email, check the box score, check out a video game, check out that video dame—all on a tiny phone. Once upon a time, this was Star Trek stuff. Madness has been stolen from the mad, sadness has been stolen from the sad.

The bike messengers that glide through Tom’s paintings, those centaurs from Middle Earth—half man, half cab—seem behind the times, quaint shadowy stencils disappearing from this newest incarnation of the city, New York 2.0. The cool New York they used to own, or feel that they owned, runs at a searing pace, spewing squalls of information that compete with them, laying claim to and craving our attention.

All artists evolve. Age changes them, events—family, mortality, success and failure—change them. Influences wax and wane. These are personal, largely passive categories. The truly perceptive artist, however, notes the changes in his times, changes great and small, the cataclysms and the subtle shifts alike, and appropriates them, folding them without apology into his vision. Tom Christopher’s latest sketches, drawings and paintings demonstrate this dynamic precisely.

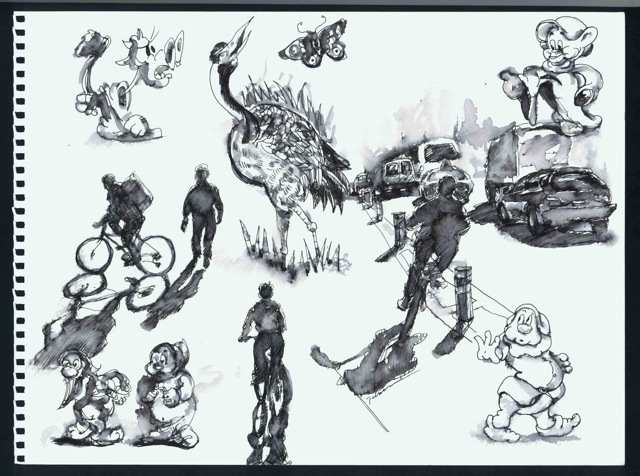

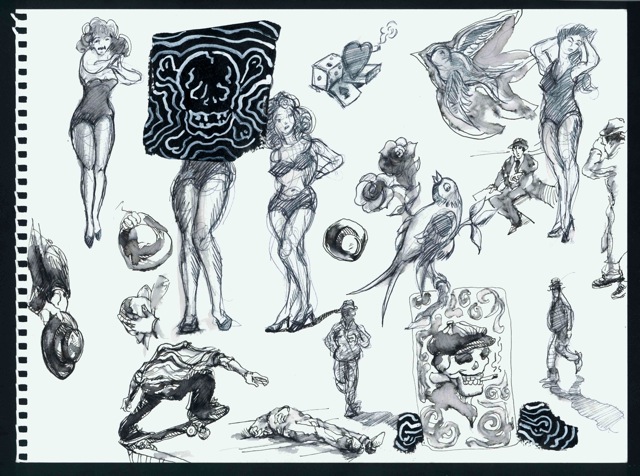

To be true to this brave new city, this allegorical bestiary of creatures caught mid-metamorphosis, Tom Christopher evolves with it, turning the latent symbols loose onto his white canvases. It’s a gesture in the direction of expressionism. Things that fill us with dread and things that that fill us with desire—mythical, archetypal forms—appear among the disjoined images that rise to the surface as we look back on the day. These panels in Christopher’s works mimic the mind’s attempt to make sense of the blur of a day in the city, isolating cells in a hive of constant activity, taking a screenshot from a running film, separating temptations from opportunities, trying to hit the pause button on a moment of beauty we almost missed.

Where vacant eyes and open mouths and archetypal tiki gods lurk in the windows of buildings, traffic lights and tail lights in a work like Yes, yes. A premium sportcoat sounds very good right about now, in A Day in the Life, empty bone sockets leer from an actual skull that puffs on the nail of its own coffin. In the cigarette smoke that hovers above the skull, a woman takes shape. Perhaps it’s the young woman below, coming up out of subterranean subway maw, the one who thinks she’s run the gauntlet. She seems easy prey for the skull. The shark that swims out of the sewer, an urban legend come to life in the cold light of day, is fate or perhaps a sign that will lead her away from doom. Perhaps. Christopher juxtaposes the images without a formal connection. The eye of the viewer connects them and writes the story.

Mermaids and genies that hide in a work like Thru Midtown; a soft wind, a flag and some steam take physical form in A Day in the Life. A shadow man crosses a road. On one side, “Man’s ruin,” a tattoo crucifix of vices—a martini and a femme fatale—shimmies. On the other side, Cupid flutters. This is a crossroads, a choice. We see the signs without knowing what it means, what the stakes are. The shadow knows. Meanwhile, oblivious, reminding us that the world doesn’t stop while we weigh our options, a bike messenger streaks by in a contemporary take on Bruegel’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus where the ploughman, angler and shepherd go about their business, indifferent to the falling, drowning man.

The siren song of the city hardens us. Its promise, to be open to the pursuit of all our dreams, the famous “pursuit of happiness,” drowns out the cries of others. Art is not immune to that tune. In Journey, a triangle of Pollock-splashed gold sits in a shadow of pure gold. The triangle might be one side of a pyramid, or a road hurtling to a vanishing point. The image figures forth the artist’s dilemma. One can’t become Pollock by painting like Pollock. Even Pollock didn’t know that what he was doing would turn him into Pollock. Fame in art, achieving the new in art that leads to fame, isn’t a paved road at all. No. This road is a mirage like the red convertible, a sign of someone else’s success that glides along at the periphery of vision, chauffeur driven in the oil paint slick of its own reflection. No Oz waits at the end of that yellow brick road. There’s nothing there where the road vanishes, nothing other than a looted tomb.

— Essay by James Balestrieri